34

Like Us on Facebook:

BetterFarmingON

Better Farming

February 2017

SATELLITE

IMAGERY

(pixel size), temporal resolutions

(repeat frequency) and spectral

resolutions (number of wavebands

that are imaged). Some sensors will

be more suitable than others for

certain applications.”

Agriculture and Agri-Food

Canada has a geospatial viewer where

the public can access these data

products. The viewer “allows you to

view and analyze image products

– the final output of our integration

of imagery to create customizable and

usable information.”

The advantage of using the geospa-

tial viewer is that the actual output

data files on their own – which are

also available through the Govern-

ment of Canada’s open data portal –

are of limited use without specialized

software and the associated expertise

needed to interpret them, he says.

“Farmers can see and use the data

if they want, but the real power is in

the information provided to agencies

that support the farmers,” says

Davidson.

The frequency with which the

satellites take images is also import-

ant, says Marsh.

“Numerous (satellite) groups

around the world are racing to build

constellations of microsatellites no

larger than a box of shoes,” he says.

“With hundreds of those shoeboxes

orbiting earth, individual groups are

expecting to (capture) the earth every

single day. That frequency of data will

make satellite imagery

(more) actionable

because it will be

much more reliable.”

Schacht similarly

stresses the impor-

tance of frequency.

“When you look at

crop health, it’s crucial

to look at your crop at

the right time,” he says.

“It’s being able to have

the image available at a

reliable cadence and

having it available

opportunistically at the farmer’s

interest.”

Planet Labs currently has 60

satellites in orbit now and is planning

to launch another 116 in the coming

months.

“We have been able to offer

service-level agreements to 85 per

cent of the earth every two weeks,

factoring in clouds. If there were no

clouds, we could provide a re-visit

rate of every week,” he says. “Satellites

also need to be able to source reliable

imagery in terms of geography,

(while) providing a resolution that is

relevant for operations at a field

management level.”

Wainscott similarly stresses the

consistency of the satellites.

“The satellites are 100 per cent

reliable that they will fly, but when

the satellite does fly over (it will either

be) cloudy or clear,” he says. “You are

at the mercy of Mother Nature.”

Because of the uncertainty of

weather, it’s important to have many

satellites in orbit to ensure access to

many images.

“Our goal is to get an image every

10 to 14 days,” he says.

Providers like HDC, Farmers Edge

and WinField United can make

images available to a farmer’s or

agronomist’s device – whether it’s a

smartphone or tractor computer –

fairly quickly and effortlessly.

Schacht, for example, says he is

able to provide retailers or clients

with their images in 24 hours or less.

“In the context of precision ag,

timely information is important,” he

says. “You (typically) need 24 hours

or less to make a

decision.”

Another important

logistical component

of satellite imagery is

the scale.

For example,

“RapidEye (the

satellite) can image 6

million square

kilometres per day.

The resolution for

RapidEye is measured

in five metres; for per-

spective, a drone may

have a resolution of

around five centimetres,” says Marsh.

But this fine resolution is not

necessary for satellite use in ag at this

stage, says Tracey-Cowan.

“On some of our agriculture land,

two-centimetre data is too detailed

for what we are achieving” with

satellite imagery, she says. “If we are

using satellite imagery to assess zones

in the field which can benefit from

being treated or managed differently

(with the variable rates of inputs),

then the resolution only needs to

Ryan Schacht

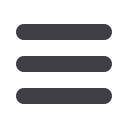

Using a colour scale and the normalized difference vegetation

index (NDVI) of a crop field, tools such as the R7® tool can display

zones of differing biomass, density and health of the crop.

Nathan Wainscott, Winfield United photo