Better Farming

November 2016

FarmNews First >

BetterFarming.com23

L

ittle did Larry Van Severen know when he was

growing up on the family’s tobacco farm near

Langton, Norfolk County that his enjoyment of a

neighbour’s swamp would one day help inspire an ambi-

tious effort to protect a much larger body of water.

Back then, Van Severen enjoyed the swamp for its

unending supply of frogs and snakes and opportunities to

muck around.

The neighbour, however, didn’t share Van Severen’s

affection for the spot and in the 1960s filled in the area. A

municipal drain soon followed to serve about 600 acres; it

travelled through the back part of the Van Severen family

farm.

In the early 2000s, Van Severen applied for a grant

under a now-defunct water-supply enhancement program

to transform a two-acre area through which the drain ran

on his farm into wetland.

“We took a 24-inch underground drainage pipe,

brought it above ground and created — with motor

scrapers and draglines and stuff like that — a diverse

depth of water. We put a little island in the middle and

shallow areas and deep areas,” says the now-retired farmer

who is in his late 60s. The project cost more than $30,000

(two-thirds of which came from his own pocket, he says).

He and his wife, Dolores, planted bulrushes, lilies and

other native plants to filter the water.

Today, the frogs have returned.

So, too, have county drainage staff to occasionally grab

water samples from the municipal drain both up and

downstream.

The drainage staff discovered in the samples at Van

Severen’s wetland and at another restored wetland that

phosphorus and nitrate levels were lower downstream.

The findings could point to a way to employ such projects,

and perhaps even municipal drains themselves, to prevent

dissolved phosphorus in field runoff from reaching Lake

Erie.

The wetlands are among 30 projects of different scales

that the county has helped to introduce since the mid-

1980s, says Bill Mayes, Norfolk’s senior drainage superin-

tendent. (The projects started as a way to protect source

water in the municipality.)

“Within the wetland there is uptake of the phosphorus

and nitrate,” Mayes says. “How much, everybody argues.

‘Oh you’re not getting the sample at the right time.’ But

when you see two numbers side by side, and they’re

different, there’s obviously something happening.”

Provincial ministries tell the municipality that the

numbers are not overly significant. Nevertheless, Mayes

says the county is now seeking partnerships to explore

doing more in-depth study.

In the meantime, the county’s findings add fuel to a

one-of-a-kind partnership between two other organiza-

After the field and before the lake

Effort to recoup phosphorus runoff faces hurdles and unknowns but could deliver cost savings to

farmers while protecting open waters, say organizers.

by MARY BAXTER

RUNOFF

CONTROL

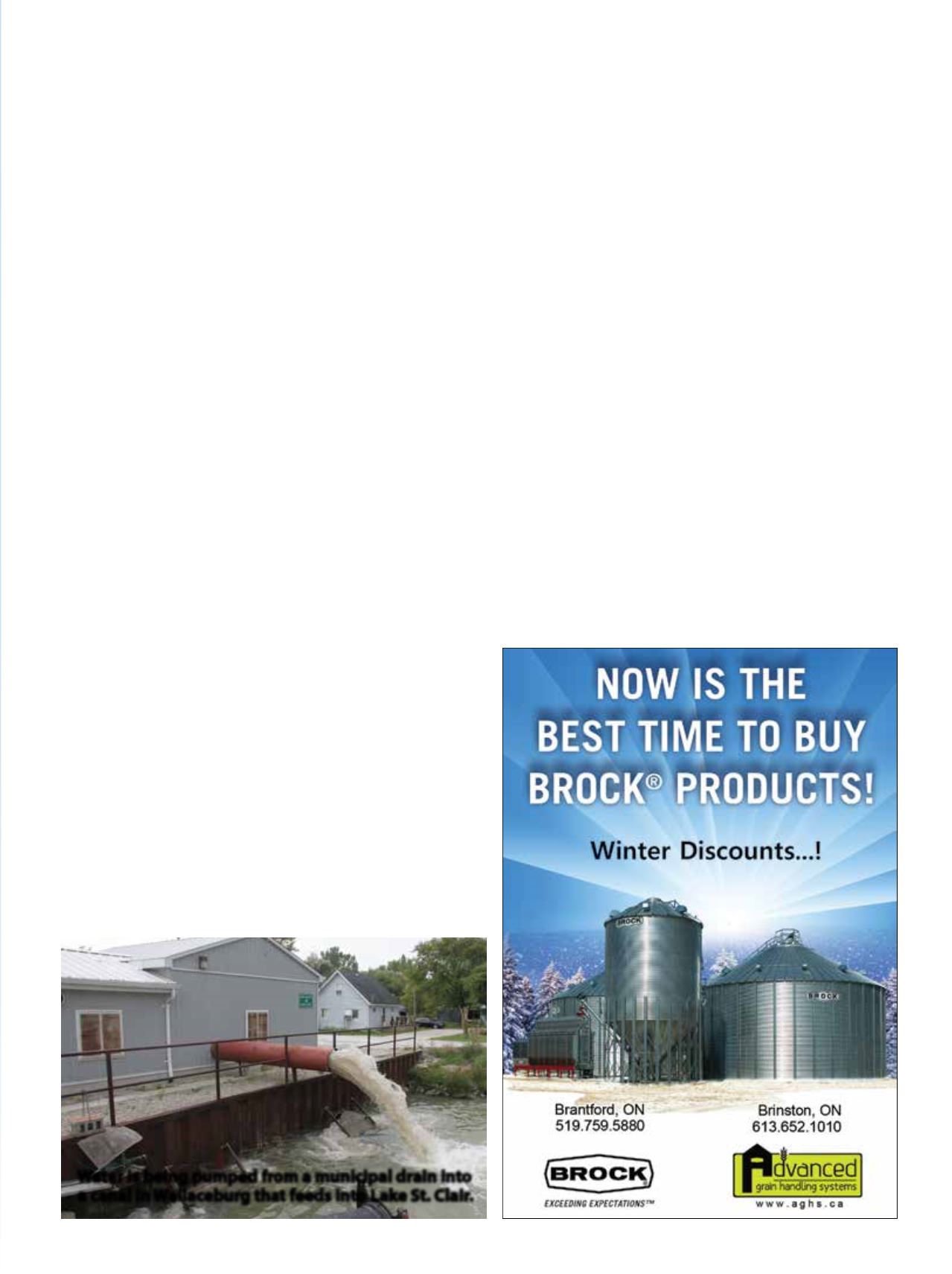

Water is being pumped from a municipal drain into

a canal inWallaceburg that feeds into Lake St. Clair.