28

Dig Deeper:

BetterFarming.comBetter Farming

December 2016

ALUS

ing a meeting of interested communi-

ty members who need to show

“ongoing commitment” to ALUS, says

Reid.

One of the first ALUS projects

grew out of just such a stewardship

meeting, which took place in late

2001 in Norfolk County. By 2004, the

Norfolk group had published a

proposal for a pilot project, which

spawned further expansion in the

county. ALUS Canada is built on this

Norfolk model.

What makes the projects success-

ful, Reid says, is that they differ from

any other conservation program.

Farmers maintain their own land,

“which they know best.”

Challenges

ALUS has faced some difficulties as it

has expanded.

One such issue arises from the rela-

tionship between farmers, who own

the land, and ALUS, a third-party

group which requires access to it.

In March 2009, for example,

Ontario Pork sent representatives to

an ALUS Alliance meeting, and the

Ontario Pork environmental commit-

tee later considered the ALUS

program.

“Although the general principles of

the program were encouraging, the

Committee had some reservations,”

says a statement secured from Sam

Bradshaw, Ontario Pork’s environ-

mental communications specialist.

In particular, Ontario Pork was

concerned about “third party involve-

ment on producer land,” the state-

ment reads.

Other farmers might have similar

reservations when they consider

making a deal with ALUS. An ALUS

project, for example, allows ALUS

program coordinators or farm

liaisons to visit a farmer’s land to

monitor the projects. Usually the

visits occur once a year, Reid notes,

but other projects, like those at M&R

Orchards, require more frequent

inspections.

However, Dave Reid notes that

farmers need not worry about

working with ALUS. Farmers are not

being regulated by ALUS, he says,

since contracts are “voluntary, and

farmers can quit at any time.”

If farmers back out early in the

project, they would have to repay the

start-up costs to ALUS, but such

occasions are rare.

Additionally, since ALUS

community groups start up the

projects themselves, they have some

control over the system itself.

Reasons for success

Despite encountering such speed

bumps along the way, ALUS has

expanded as farmers notice the

benefits that the projects bring to

their communities.

Farmers often find that after the

instalment of an ALUS project on

their land they develop a new sense of

awareness of wildlife and the environ-

ment, Reid notes.

Even if they acquire just a one- or

two-acre project, farmers will undergo

a mindset change, and they will begin

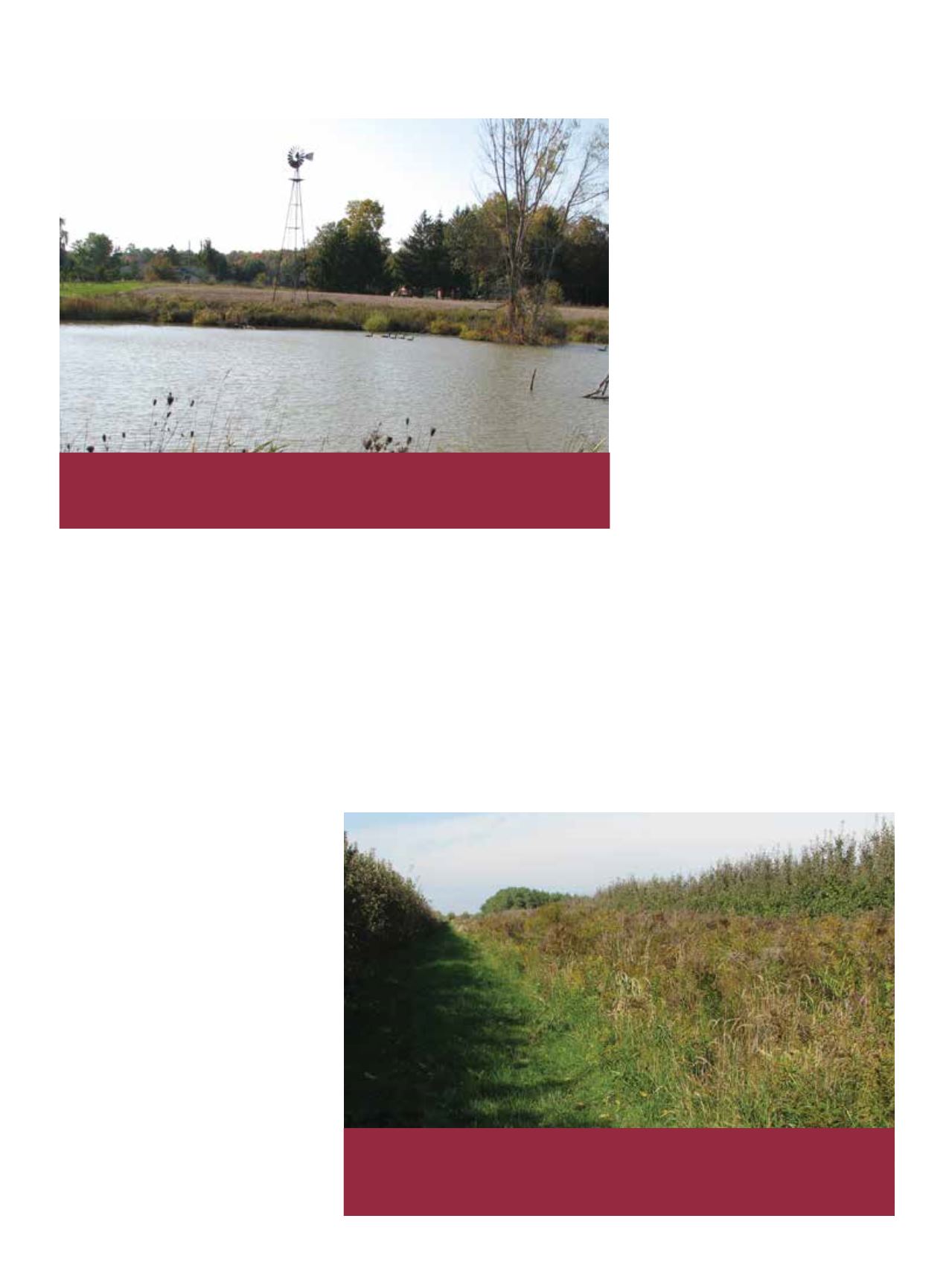

ALUS redeveloped a historic wetland, which had previously been

filled in, at M&R Orchards. The wetland is now home to native flora

and fauna.

M&R Orchards has two pollinator strips (occupying 1.5 acres total)

developed by ALUS, on which native species can be found. This strip

features Indian grass, brown-eyed Susans and big bluestem,

among others.