16

Better Pork

June 2016

Both Kelly and Jamieson urge farm-

ers to develop a fire plan for emergen-

cies. “That’s of some value in terms of

minimizing losses,” Kelly says. Consult

your local fire departments, they advise.

But Sebringville producer Doug

Ahrens says it’s not only farmers who

need to take

action. Vendors

of electrical

equipment and

fixtures must

do more to

make available

good quality,

inexpensive

equipment

resistant to cor-

rosion.

“Farmers are concerned about what’s

going on and try to do their best. We’re

caught in a price squeeze too, but we’re

made out as the villain,” he says. “But

we’ve got a whole raft of villains over

top of us. If they just pull it all together,

we could put this thing together at a

reasonable price.”

Emergency plan?

John Van Engelen chuckles when he

hears the idea of tying heat sensors

into an alarm system and training the

sensors on fans. There are so many fans.

“And there’s where you’re talking about

a big cost.” Maybe developments such

as nanotechnology will eventually make

that strategy affordable, he says.

Asking if he has an emergency plan

for the barn elicits chuckles too, but

only after a surprised silence. There are

only two of them who work in the barn

full time. Occasionally his daughter

helps out. Everyone can navigate the

facility blindfolded.

Van Engelen eyes Mitchell, seated at

the barn office desk. “Did you do one

when you were at Guelph?”

“No,” Mitchell admits. “I know

there’s supposed to be one.”

If there’s an emergency in the barn,

says the older Van Engelen, “we’d just

call 911.” If it’s a small fire, they’d try

to handle it first on their own with fire

extinguishers. They’ve used extinguish-

ers before (to tackle combine fires). But

if it’s large, they’d call 911.

What else can be done? I put that

question to Larry Jacobson, professor

and extension engineer in the Univer-

sity of Minnesota’s department of bio-

products and biosystems engineering.

In 2010, Jacobson headed a National

Pork Board committee which explored

what the 21st-century sustainable hog-

finishing barn should look like.

“Let’s get the manure out of the barn

and let’s store it outside,” he says. That

way, in the barn, “you still have a corro-

sive environment, but it’s probably not

as corrosive.” You’re going to have to

have the same “level of electrical robust-

ness in the wiring.” Ventilation is still

needed as well as “a lot of other things.”

Nevertheless, the move eliminates many

of the risks.

Jacobson’s solution doesn’t sit well

with Van Engelen for a multitude of

reasons. At the top of the list is the

increasing difficulty in obtaining a

municipal building permit for a facility

that has an exterior manure pit. Instead,

try regular maintenance combined with

a ventilation system like his own, he

suggests.

“If you have a 100 per cent pit-

ventilated barn that never lets the gas

come up in the first place, that you can

actually agitate and you will never smell

it inside the barn, only outside the barn

where the fan is, maybe that would be a

lot better.”

BP

COVER

STORY

Doug Ahrens

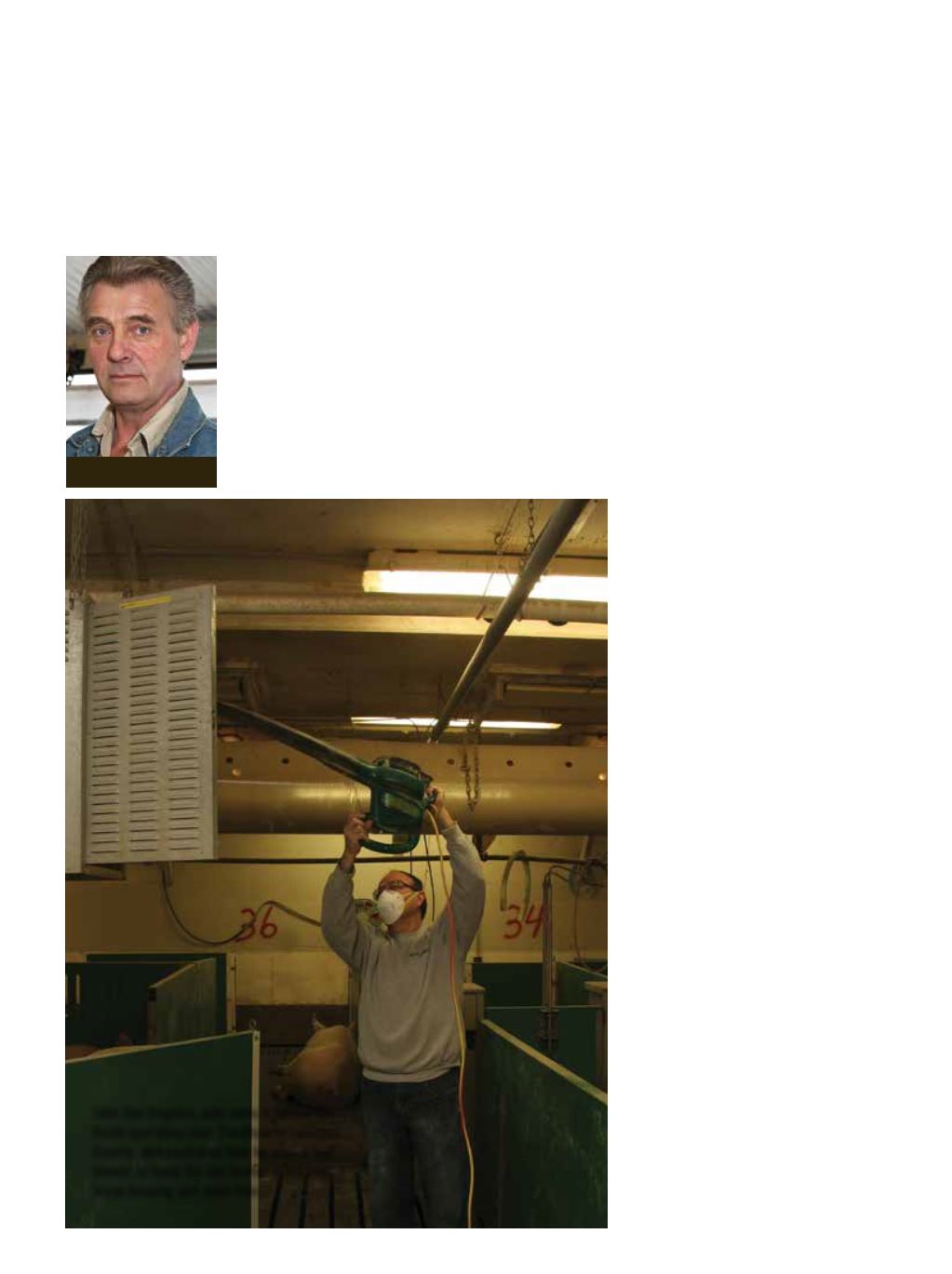

John Van Engelen, who owns a farrow-to-

finish operation near Thedford in Lambton

County, demonstrates how he uses a leaf

blower to keep the fan heater in his sow

loose housing unit dust-free.