How Do We Help Pigs During Heat Stress?

By Maude Richer-Lanciault & Marion Mogire

For many of us, the hot days of summer are a welcomed change from our long Canadian winters – but for our pig barns the warm and humid weather conditions can create the opportunity for performance and profitability losses.

Meteorologists predict that we should expect above-average temperatures in the coming years, and that summers will start earlier than in previous years. With this, heat stress in pig production will become a bigger concern across Canada.

Why are pigs sensitive to heat stress?

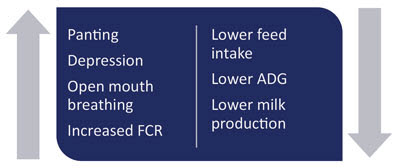

Pigs are more sensitive to heat stress than other animals because they do not sweat. To lower their body temperature, pigs will dissipate heat to the environment and decrease metabolic heat production. Therefore, their feed intake will decrease, and performance will be lost.

The genetics and biological composition of commercial hogs has changed considerably in recent years; we have seen a significant decrease in fat deposition of modern animals. From 1991 to 2001, the body lean tissue rate has been increased by 1.55 per cent, which led to higher metabolic heat production by 14.6 per cent (Brown-Brandl et al., 2004). The increase in body heat production requires an adjustment of the ventilation to remove this heat.

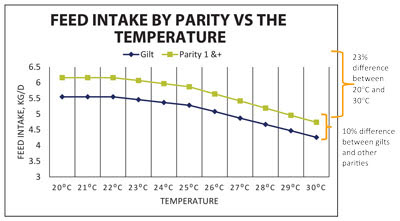

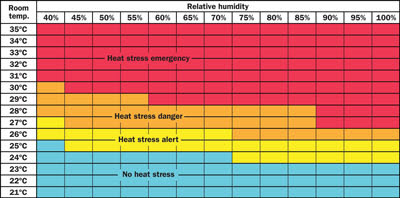

Pigs have a thermoneutral zone of 18 C to 23 C. At temperatures above 23 C, pigs begin to experience heat stress and the feed intake of the sow will start to be affected. Between 20 C and 30 C, the feed intake will be reduced by up to 23 per cent. Ambient temperature is not the only factor that causes heat stress – it is also determined by humidity.

Depending on relative humidity, the apparent temperature will be different and is what the sow will feel. For example, a barn with high humidity of 80 per cent will be in heat stress danger at 26 C, while another barn with similar temperature and at 70 per cent humidity will be on heat stress alert (Figure 2).

High humidity combined with high temperatures is the environment we want to avoid for our animals, and this takes additional management of barn environments to prevent or eliminate the heat stress conditions.

What can we do to support our sows during a heat stress period?

The environment in the barn should be monitored and adjusted appropriately (ventilation, cooling system, heat pad and lamps for piglets). It is important to keep the sows and piglets comfortable. Air quality should be assessed, too, for the welfare of animals and workers.

The water – quality and quantity – is extremely important for the sows. Water should always be available and be of good quality. Water quality assessments should be done before the summer (mineral, microbiology) and a verification of the flow in multiple points along the water line should be completed. The barn should have enough water points/drinkers for sows in the group housing section. Access to fresh water is important for sows at all times, but during heat stress it is especially critical.

You can see a change in feeding pattern of sows – follow their lead and match this pattern to your feed allocation program. The lactation feed should be available during cooler periods of the day (early morning and late night). The feed should be kept fresh and clean to stimulate feed intake.

Your nutritionist can work with you to find the best nutrition strategy for summer management in your barn. Many options are available, such as: Adjusting feeding program and schedule, use of specific additives, or changes in diet formulations.

Feeding programs & formulation

Several tools can be used to adjust your program during heat stress. One example is a commercial animal model. Animal models can help determine the target feed intake according to different temperatures and evaluate the best feed density. Models help to customize for the reality in the barn according to environment, genetics, performance, and management. Your nutritionist can support you in utilizing an animal model and optimizing your feeding program with its outputs.

An adjustment of the density of feed is used to support the lower feed intake observed during summer. Specific adjustment of nutrients such as amino acid ratios with energy, protein level and fiber will keep the ration balanced with this higher density. It is important to keep the feed very palatable to stimulate feed intake.

Feed additives

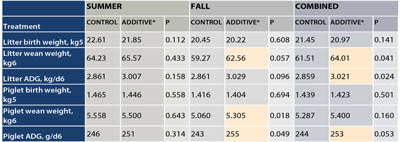

Oxidative stress impacts high-producing animals, especially under challenging conditions like heat stress. Antioxidant feed additives can be used to reduce damaging effects of oxidative stress. Addition of an antioxidant package in the feed can support the animal during the heat stress period. Vitamin E and selenium are the most common antioxidants in the diet. In addition, natural polyphenols, extracted from fruits and spices, have been shown extensively to reduce oxidative stress in animals (Table 1). Another additive with a potential to alleviate heat stress is betaine. Dietary supplementation with betaine has shown to reduce markers of oxidative stress and improve performance in hot and humid environments.

A total of 136 sows were used in this study, conducted in a commercial sow facility in Manitoba. Two treatments were applied – Control containing basal diet and 60 ppm vitamin #; and Additive* containing basal diet, 60 ppm vitamin E and 60 ppm additive. Both diets were fed from seven days pre-farrowing to 20 days after farrowing date. Piglets were weaned between days 18 to 20. Sow and piglet performance were measured at farrowing and weaning. The litter and piglet birth weight, weaning weight, litter and piglets average daily gain were evaluated.

The addition of a polyphenol blend has been demonstrated to increase sows’ reproductive performance compared with a control group of only vitamin E. Polyphenols reduce lipid peroxidation before and during health stress, by decreasing malondialdehyde (MDA) production. The addition of this blend containing polyphenols was shown to increase lactation feed intake in sows by two per cent, numerically increase the number of piglets weaned by a 16 per cent drop in preweaning mortality and increase litter weaning weight by four per cent with no increase in feed cost for each piglet weaned. Working with your nutritionist, you can select feed additives to provide the best return on investment and fit with your needs during the summer months.

In summary, heat stress impacts performance at multiple levels and has big impacts on sow farms. Both farm management and nutritional solutions can be integrated to help support pig producers.

Farm management strategies include:

- Good water quality and quantity available for all pigs.

- Adjustment of the environment for the temperature and humidity in the barn.

- Make sure feed is available in the cooler times of the day.

Feeding strategies include:

- Keep your feed palatable and fresh.

- Explore feed additives that support sow performance.

- Adjustment of the feed density.

Utilize animal models to support your nutritional decisions. BP

Post new comment