Farmers must ensure that their breeding animals meet daily nutrient and energy requirements to maintain healthy herds and litters.

by Kate Ayers

Breeding sows can be likened to Formula One race cars, says Mark Bodenham, the swine business manager at Masterfeeds at the London, Ont. office.

This company provides farmers with animal nutrition solutions.

Recently, scientists and industry experts have made tremendous advancements in swine genetics; the results are prolific litters and increased demands on gilts and sows. So, herd health personnel – including farmers and nutritionists – need to optimize how they manage these animals.

Raising a productive sow starts with good animal husbandry at birth and extends into the animal’s gilt growth stage.

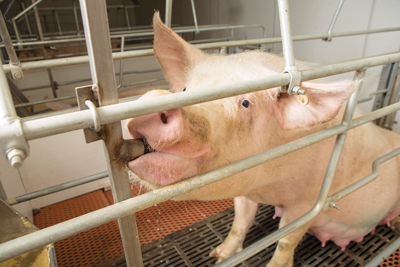

Christina W. Kroeker Creative photo

“When you are looking at life-time performance of a sow, the value of proper gilt development cannot be understated,” says Donald Skinner, manager of nutrition and technical services at Molesworth Farm Supply in Listowel, Ont. This business helps farmers develop feed plans for their swine, poultry and ruminant animals.

“Regardless of how you get replacement females into your sow herd, the end game is making sure that, early in their life cycles, they’ve been fed and raised to be breeding animals.”

Swine nutrition specialists, extension specialists and a Manitoba hog producer share tips to help farmers manage the challenges associated with breeding-sow feed regimens. After all, productive and healthy sows produce strong piglets.

Factors affecting feed intake

Each gilt and sow has unique needs. So, responses to environmental conditions may vary across the herd.

However, all lactating sows need adequate nutrient and energy intake to support their health and produce viable litters.

Factors that may affect a lactating sow’s feed intake include

- body condition before farrowing

- genetics

- age and parity

- feed quality, frequency and composition

- barn temperature

- feeder type

- water availability

- barn personnel

“Sow feed intake during gestation and body condition prior to farrowing” are crucial, Dr. Denise Beaulieu, an assistant professor in the department of animal and poultry science at the University of Saskatchewan, says to Better Pork.

“That is primarily why we limit feed intake during gestation. If the feed intake is too high during gestation, that will negatively affect feed intake during lactation, especially right after farrowing.”

Skinner agrees.

“If a sow is overweight, she produces a hormone that reduces her appetite,” he says.

“Reproductive issues can arise as well because the animal will start to put fat tissue into her mammary glands.” And she might not milk as well. “These issues can affect a sow’s rebreeding and future litters.”

Producers can visually assess animals’ conditions, looking particularly at back fat and using a scoring system. While this approach is quick, it is also subjective.

“The trouble with visual scoring is that some sows are tall and lean looking but still have back fat. Other sows may be stout and not have very much” back fat, Skinner says.

“Not all sows are created equally in physical appearance.”

Farmers can use ultrasound probes or calipers to directly measure back-fat thickness. These tools are more precise than visual scores, but they are also more expensive and time consuming.

In addition to monitoring sows’ body conditions, producers must monitor lactating sows’ feed quality and eating frequency.

As first-parity sows are smaller in size and do not produce as much milk as multiparous sows, these animals have a feed intake that is about 10 per cent lower than multiparous sows, says Laura Eastwood, the swine specialist at the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs.

So, farmers should ensure these younger sows get enough feed to maintain proper conditioning.

“By increasing feeding frequency from two to three times a day, intake will increase about 15 per cent,” Eastwood says.

Lactation diets

Feed for lactating sows must contain three essential components: adequate energy and protein to sustain high productivity and quality ingredients to encourage the animals’ higher feed consumption.

Christina W. Kroeker Creative photo

“Energy demands for milk production are very high, especially with larger litters, so a high-energy intake is important,” Skinner says.

“But protein and amino acid content cannot be forgotten. Really, it’s about having an appropriate balance between the two.”

Commonly, nutritionists use corn and soybean meals in lactating sows’ diets. Farmers can also include wheat shorts in the ration as a source of fibre as well as by-products, such as bakery meal and liquid fat sources.

Lower cost is a reason farmers may use those products, Skinner says. These feed ingredients also provide fibre for nursing sows, which has shown to provide gut health benefits and prevent constipation, Skinner says. Constipation leads to reduced feed intake, which hurts milk production and piglet growth.

“You can also use corn distillers and canola meal. But some people are conservative with their use” of these ingredients.

They are concerned about feed palatability and want to limit “potential exposure to toxins that might be in corn,” Skinner adds.

In addition, nutritionists include “vitamins and minerals at higher levels in lactation diets than in other rations because such diets need to support a breeding animal, not just a growing animal.”

The staff at Starlite Colony in Starbuck, Man., feed their farrowing pigs wheat, corn, barley and full-fat soybean meal, says James Hofer, the colony’s hog barn manager. The team includes hemp seed screenings in the ration when the product is available. This ingredient is high in fibre, energy and protein, Hofer says.

The colony’s feeding system allows Hofer to feed two rations to accommodate animals in different developmental stages.

“The first ration is a gilt ration, designed for first-parity animals. It has been scientifically proven that a gilt that is farrowing for the first time is not yet finished developing, and she is still growing,” Hofer says.

“If you try to make a ration that is good for the gilts and good for the sows, you’d really overfeed your sows. Sometimes, I think people make a ration kind of in the middle, but then no animal gets the right feed.”

In addition to fibre and energy requirements, producers must also find the correct amino acid ratios for their sows. Farmers can add lysine, methionine and threonine – important amino acids – to the feed, Beaulieu says.

The swine sector should focus more on nutrients and less on ingredients, Bodenham adds.

“Ingredients are a delivery mechanism for nutrients. If you assume there are no quality issues with the ingredients, you need to develop a balanced nutrient program that will deliver” what the sows need, he says.

Given sows’ complex dietary needs, “producers need to work closely with their nutritionists, vets and genetics companies to come up with a feeding program appropriate for their herds,” Eastwood says.

“Recommendations can vary greatly based on health status, genetics, ingredient availability, time of year” and other factors, she adds.

Negative nutrient balances

Christina W. Kroeker Creative photo

Lactating sows are in a constant state of energy deficiency as they must provide a continuous supply of nutrient-dense milk for their piglets.

So, the key is to limit nutrient imbalances as much as possible throughout the lactation period, Skinner says.

When sows use more energy and nutrients than they can uptake through feed, they begin to use their fat tissue to generate milk and carry out bodily functions. If that happens to an excessive degree, sows can become more prone to illness and injury, he adds.

If severe, insufficient nutrient and energy intake can have significant effects.

Low nutrient and energy intake can cost you up to 1.2 piglets per litter, according to a 2006 study by Goodband and others, Bodenham says.

“Consequences of insufficient nutrient and energy intake are very dramatic and are probably one of the greater challenges we face” in the industry, he adds.

This nutrition issue can even threaten sows’ future production.

It can prevent sows from going into heat for the next breeding cycle and disrupt hormone levels, Skinner explains.

While lactating pigs will often lose some weight, farmers must monitor these animals to ensure their body conditions do not drop too low.

“The goal is to prevent large swings in body condition throughout her reproductive life, keeping body condition as steady as possible,” Eastwood says.

“Large swings in body condition can have negative impacts on conception rates, embryo survival, farrowing rates, piglet birth weight, litter variability, re-breeding rates, milk production (and thus piglet weaning weights), sow longevity, sow lifetime productivity and producer profitability,” she explains.

Farmers can limit nutrient imbalances by monitoring sow feed intake throughout lactation.

“Knowing sow feed intake can help you make more informed management and nutritional decisions. It can also play a role in troubleshooting other issues that might exist within your operation,” says Skinner.

For producers who manually feed their sows, “one of the simplest ways to track feed consumption is to use a sow feed card,” says Skinner.

“You have a card hanging above each sow’s farrowing crate and you mark down how much feed is going to that sow for every feeding.”

Some automatic feeders can collect this data for farmers.

After the farrowing period, farmers can review this data for individual sows and compare it with the average feed intake across herds.

Optimizing feed intake

Meeting the nutritional requirements of lactating sows can be challenging for hog producers. So, farmers should review their barn and animal management strategies to optimize the animals’ feed intake.

“Key factors under the farmer’s control are management of sows in gestation, temperature, water availability and ‘feeding style,’” Skinner says.

Maintaining the correct farrowing barn temperature is critical for maximizing lactating sows’ feed intake. But nurse sows’ needs differ greatly from piglets’ needs.

“A sow is most comfortable between 15 and 22 C (59 and 71.6 F), whereas newborn piglets need to be between 30 and 35 C (86 and 95 F),” he says.

“Keeping the ambient temperature cooler and creating two separate microenvironments for the piglets and the sows are of paramount importance,” Bodenham says.

Christina W. Kroeker Creative photo

Hofer puts plastic wrap above the creep feeder and heating pad areas to keep the piglets warm.

Producers must also ensure the correct feed-to-water ratio to optimize sow feed intake.

“Pigs don’t like to eat dry feed. They prefer to eat it with a bit of moisture, like a porridge,” Skinner says.

“But, if feed gets wet, it’s easier to spoil. And if it spoils, they are not going to eat it.”

Barn staff must keep the feeders clean, so the rations remain appetizing for the sows.

“If the pigs can have waterers in the feeder and the feeder stays relatively clean, that’s the best way to maximize feed intake,” Skinner adds.

Eastwood agrees. “Pelleted feed or wet feed will increase intake by approximately 10 per cent compared to dry mash,” she says.

National Pork Board, Des Moines, Iowa photo

“Sows need good access to quality water at all times. Including water nipples that they can access while laying down, in addition to ones for when they are standing, is a great idea.”

Barn feeding systems also play a role in ensuring sows have access to the necessary nutrients throughout the farrowing period.

In Skinner’s experience, ad libitum (ad lib) feeding may be the most effective method to ensure lactating sows are comfortable and satisfied, he says.

They “should be able to eat as much as they feel like eating,” he adds.

Hofer agrees.

“Our sows are on ad lib feed the minute they are loaded into the farrowing crates,” he says.

“That is one way that we ensure the sows are getting enough feed. They are not limited in any way as to how much they can eat.”

Other producers, however, prefer to hand feed during lactation, Eastwood says.

So, “producers must find a feeding system option that is right for them, their staff and their facilities,” she adds.

Skilled and knowledgeable barn personnel can oversee these management details and greatly promote animal productivity.

Staff in the barn “definitely need to understand what is going on and what they see in the farrowing rooms for intake,” says Bodenham.

If we optimize feed and barn conditions, we can wave the checkered flag for achieving top productivity in our sow herds. BP

Post new comment